While studying the history and philosophy of Praise & Worship music, I encountered a particular study that is commonly used by its proponents. As noted in Ruth and Hong’s A History of Contemporary Praise & Worship, much of the basis for Praise & Worship has been found in the book of Psalms. This is found even in its earliest days (1940-50’s):

“Part of [James] Beall’s presentation of this restored divine order was a use of proof texts from Psalms to justify specific practices: Psalm 150 to ground the use of a variety of musical instruments, Palm 134 or the lifting of hands, and Psalm 47 for clapping hands. In the surge of teaching materials in the next historical periods such us of proof texts – especially from Psalms – would become a standard teaching device.”

– A History of Contemporary Praise & Worship, p. 41 [Emphasis added]

“The use of psalm proof texts to develop a liturgical schema points to the fourth core theological conviction: Praise & Worship was approached as a biblically derived, God-given pattern for worship. Convinced that this was the way of worship God had given in the Bible, its practitioners taught it with the confidence they had in the Scriptures themselves. Their tone was neither experimental nor cautious since Praise & Worship was not human-created, according to this theology. Rather, it was God’s gift to renew the church. Consequently; the Bible as God’s Word outlined its underlying promise (God desires to dwell with his people and does so through their praise) and its specific methods.

“Not surprisingly, this conviction about the biblical basis for Praise & Worship generated a method for theologizing. It had three regular features: The first was a predilection for undertaking studies of biblical words and then using key words to compile a group of passages from which to form a synthesis. For example, what Reg Layzell did in 1946 (see chap. 1), Judith McAllister did forty years later when the criticalness of praise first hooked her: she immersed herself for days in Bible study tools like concordances, skipping nearly a week of college classes. Her goal was to see when and how the Bible used the word “praise.” The second regular feature was an attraction to typology drawn from Bible stories, especially from the Old Testament and especially from narratives about David. (The book of Revelation was a favorite of some too.) Praise & Worship teachers used these stories to develop types instructive for how and why Christians should worship. The third regular feature of the theological method was, as mentioned above, a predilection for using the Psalms to provide the details about the specific dimensions of Praise & Worship, especially those involving physical expression. Therefore, the biblically derived theology of Praise & Worship was a very embodied theology, because the Psalms drew a picture of worshipers fully engaged with their whole persons.“

– A History of Contemporary Praise & Worship, p. 127 [Emphasis added]

The same process of using the Psalms, its imagery and its vocabulary, is alive and well today. A quick search on Amazon will reveal works like Worship Actions & Attitudes: Understanding 10 Hebrew Words For Praise and Worship by Rob Stiles, Holy Roar: 7 Words That Will Change the Way You Worship by Chris Tomlin and Darren Whitehead, and The Power of Praise: The 7 Hebrew Words for Praise by David Chapman. There is not shortage of online resources on the subject either: such as here, here, or here.

Before we move on, let me say that just because a person uses Scripture or language studies to back their beliefs it does not guarantee that they are correct. Verses can be taken out of context (looking at you, Jeremiah 29:11) and words can be redefined. You can also use faulty scholarship or logic. Too often I see people, even those I agree with, defend their positions through eisegesis and not exegesis. As a side note, let me say as someone that is pro-KJV that I get nervous when I see someone who generally doesn’t use the KJV quote from it (see uses of Proverbs 29:18 for an example). It is a sign of cherry picking verses with just the right wording in order to support an argument, which is an application of eisegeses.

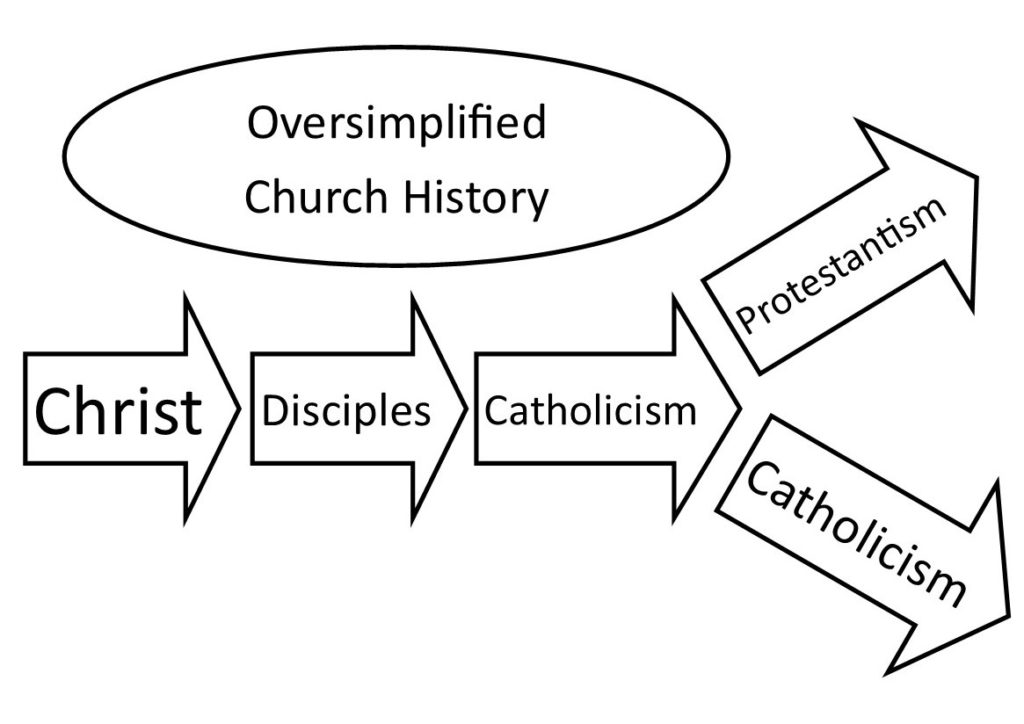

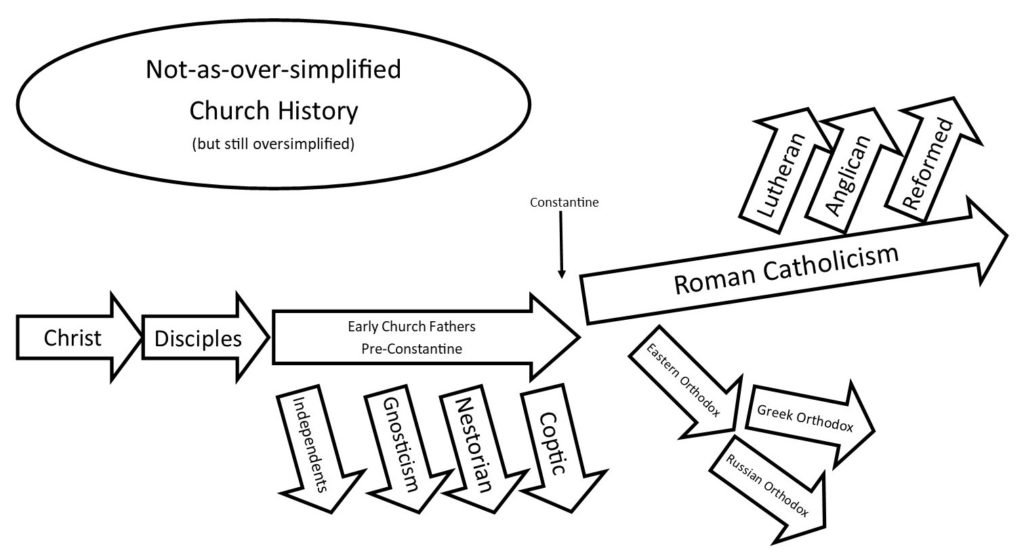

As far as I can tell, no one across the multiple millennia of the history of worshipping the God of the Bible ever used the Hebrew language (including Psalms) to discover or defend charismatic-style ecstatic worship practices until the mid-twentieth century. Centuries of rabbinical thought and debate did not uncover it. Centuries of Bible scholarship did not discover it. Millions of believers who earnestly sought how to properly express their worship and praise through diligent study of Scripture did not discover it. Who did discover this? According to the afore mentioned A History of Contemporary Praise & Worship it was likely the Latter Rain branch of the Pentecostal movement that developed and propagated it as they believed God had “restored” through them the lost and forgotten truths of how He wanted to be praised.

But I am not putting this together to talk about history (please, just go and read A History of Contemporary Praise & Worship already). I want to present a more balanced exegetical study of the Hebrew word studies they promote. I do not claim to be any sort of expert on the Hebrew language, but most of the pro-P&W writers who have also written on this subject are clearly not either. The entire presentation is obviously built around looking up words in a Strong’s Concordance.

Alphabetical List of Words

Halal

- Hebrew: הָלַל

- Verb

- Strong’s: H1984 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 165x total, 94x in Psalms

- KJV translations: praise (117x), glory (14x), boast (10x), mad (8x), shine (3x), foolish (3x), fools (2x), commended (2x), rage (2x), celebrate (1x), give (1x), marriage (1x), renowned (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to be clear (orig. Of sound, but usually of color); to shine; hence, to make a show, to boast; and thus to be (clamorously) foolish; to rave; causatively, to celebrate; also to stultify — (make) boast (self), celebrate, commend, (deal, make), fool(- ish, -ly), glory, give (light), be (make, feign self) mad (against), give in marriage, (sing, be worthy of) praise, rage, renowned, shine.

The common P&W definition is “to praise, to make a show or rave about, to glory in or boast upon, to be clamorously foolish about you adoration of God”. I that find exact definition copied and pasted across multiple websites without acknowledging its original source.

I find a much truer emphasis should be placed on the ideas of “shining”, “focusing”, or “revealing”. It used to describe light sources emanating their light (Job 29:3, 31:25), revealing through action an inner madness or insanity (I Samuel 21:13, Jeremiah 50:38), boastful claims from a prideful heart (Psalm 10:3, Proverbs 27:1), and revealing outwardly an inner foolishness (Job, 12:17, Psalm 75:4)

There is no hint of “raving” or being “clamorously foolish” in the proper use of halal. Those that claim so misapply the connection with madness to the broader application of the word.

The best way I can describe the true meaning of halal is the idea of a spotlight. When we praise God, we are not focusing on ourselves but spotlighting His worthiness and greatness. When we boast, we are spotlighting our prideful self. When someone is foolish or insane, their actions are spotlighting their inward condition.

So when we praise God, we are putting all the attention and glory and honor onto Him. When halal is applied to praising God it has little or no focus on the one praising. When we praise Him we step into the shadows and so that He can shine.

For further reading, see this post by Daniel Rodriguez.

Barak

- Hebrew: בָרַךְ

- Verb

- Strong’s: H1288 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 330x total, 75x in Psalms

- KJV translations: bless (302x), salute (5x), curse (4x), blaspheme (2x), blessing (2x), praised (2x), kneel down (2x), congratulate (1x), kneel (1x), make to kneel (1x), miscellaneous (8x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to kneel; by implication to bless God (as an act of adoration), and (vice-versa) man (as a benefit); also (by euphemism) to curse (God or the king, as treason) — X abundantly, X altogether, X at all, blaspheme, bless, congratulate, curse, X greatly, X indeed, kneel (down), praise, salute, X still, thank.

The common P&W definition is “to kneel or bow, to give reverence to God as an act of adoration, implies a continual conscious giving place to God, to be attuned to him and his presence”. This definition is also copied and pasted around the internet, including many with attuned misspelled as atuned.

This word carries the ideas of kneeling before someone as in homage or reverence (II Chronicles 6:13, Psalm 95:6), to acknowledge through salutation (I Samuel 13:10, II Kings 4:29), to pronounce a desire of goodwill and bountifulness upon (Genesis 12:2-3, 49:28), or to be specially granted goodness and favor (Psalm 5:12, Proverbs 3:33). In a negative sense, it can mean to denounce or wish evil upon (Job 2:9, I Kings 21:10).

When applied to our worship of God, we see the ideas of humility (kneeling down), acknowledgement, honor, and reverence. The primary targets of our blessing is either God Himself (Psalm 103:1-2) or His name (Psalm 113:2). This is a heartfelt reaction to God’s glory (Psalm 104:1) and His great works (Psalm 28:6). I want to press the point of humility here: when we bless God, we are acknowledging His greatness in part by bowing (literally or figuratively) before Him. The focus is on God and not the worshipper.

Where the aforementioned P&W definition errs is in its application toward God’s presence and in “giving place”. There is no consistent connection with blessing God and being in His presence. The teaching of God’s omnipresence (Psalm 139:7-18, Isaiah 57:15, etc.) greatly undermines any need to acknowledge His appearance. As to the idea of “giving place” or yielding, I see no connection at all to this word.

See also this post.

Shabach

- Hebrew: שָׁבַח

- Verb

- Strong’s: H7623 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 11x total, 7x in Psalms

- KJV translations: praise (5x), still (2x), keep it in (1x), glory (1x), triumph (1x), commend (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; properly, to address in a loud tone, i.e. (specifically) loud; figuratively, to pacify (as if by words) — commend, glory, keep in, praise, still, triumph.

- Note – an Aramaic form of the word (Strong’s H2624) is used 5x in Daniel and translated as “praise”.

A P&W definition found here is “to address in a loud tone, a loud adoration, a shout, proclaiming with a loud voice (unashamed), to glory, triumph, power, a testimony of praise”. This word does not make it onto all the word study lists, probably because of the scarcity of its usage, but it is the source for the title of Chris Tomlin and Darren Whitehead’s popular book Holy Roar.

The primary emphasis the that P&W supporters focus on is “loud” as expression of boldness in sound volume. This is interesting because not all dictionaries, lexicons, etc. agree on that emphasis. Strong’s definition shown above uses it, but the Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew Lexicon, New American Standard Concordance, Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon, and Ancient Hebrew Lexicon do not mention anything about loudness. Another Hebrew word study I stumbled across mentions shabach while discussing Shavuot and describes it as “praise, happy praise, but also: calm down, appease”. So far, Strong’s is the only language resource I have found that mentions loudness. The idea of loud volume actually contradicts the context of all but the uses in I Chronicles and Psalms.

The consensus on the root definition appears to be “to soothe or stroke”. A much safer application to praise would be “praising in/through peace”, which is the complete opposite of the P&W materials I have examined.

Since I mentioned Holy Roar earlier, let me say that that book is a terrible book (you just don’t have to take my word for it). It is extremely faulty and misleading in its presentation. When it presents shabach in chapter 7, it states with no reference or foundation: “Quite literally, it means to raise a holy roar.” (p. 99) It does recognize that word only appears 11x, “but each time, it has powerful effect.” (p. 99). It then goes on to only reference 3 of the 11. What about the other 8? Is there not enough “powerful effect” in them? The reason why other references are not used is because doing so destroys the presented definition and argument.

Here are the verses that are referenced:

- Psalm 63:3 – “Because thy lovingkindness is better than life, my lips shall praise [shabach] thee.”

- NOTE – They wrongly identify the appearance of shabach on p. 99. They place it in verse 4, which is actually: “Thus will I bless [barak] thee while I live…”

- Psalm 117:1 – “O praise the LORD, all ye nations: praise [shabach] him, all ye people.”

- Psalm 145:4 – “One generation shall praise [shabach] thy works to another, and shall declare thy mighty acts.”

Below are the verses that the “powerful effect” wasn’t enough to include:

- I Chronicles 16:35 – “And say ye, Save us, O God of our salvation, and gather us together, and deliver us from the heathen, that we may give thanks to thy holy name, and glory [shabach] in thy praise.”

- Psalm 65:7 – “Which stilleth [shabach] the noise of the seas, the noise of their waves, and the tumult of the people.”

- Psalm 89:9 – “Thou rulest the raging of the sea: when the waves thereof arise, thou stillest [shabach] them.”

- Psalm 106:47 – “Save us, O LORD our God, and gather us from among the heathen, to give thanks unto thy holy name, and to triumph [shabach] in thy praise.”

- Psalm 147:12 – “Praise [shabach] the LORD, O Jerusalem; praise thy God, O Zion.”

- Proverbs 29:11 – “A fool uttereth all his mind: but a wise man keepeth [shabach] it in till afterwards.”

- Ecclesiastes 4:2 – “Wherefore I praised [shabach] the dead which are already dead more than the living which are yet alive.”

- Ecclesiastes 8:15 – “Then I commended [shabach] mirth, because a man hath no better thing under the sun, than to eat, and to drink, and to be merry: for that shall abide with him of his labour the days of his life, which God giveth him under the sun.”

So, maybe three more might could have been used to support their argument (I Chronicles 16:35, Psalm 106:47, Psalm 147:1). But where is the “powerful effect” of raising a “holy roar” in stilling/calming (Psalm 65:7, 89:9), keeping/holding (Proverbs 29:11), praising the dead (Ecclesiastes 4:2), or commending mirth/pleasure (Ecclesiastes 8:15)? You cannot claim the word means “holy roar” or has a “powerful effect” each time it appears when in half of it uses it cannot mean what you claim. If you do some digging it appears obvious that there is no basis for equating shabach with a “holy roar” other than taking Darren Whitehead’s word for it.

Yadah

- Hebrew: יָדָה

- Verb

- Strong’s: H3034 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 114x total, 67x in Psalms

- KJV translations: praise (53x), give thanks (32x), confess (16x), thank (5x), make confession (2x), thanksgiving (2x), cast (1x), cast out (1x), shoot (1x), thankful (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; used only as denominative from yad; literally, to use (i.e. Hold out) the hand; physically, to throw (a stone, an arrow) at or away; especially to revere or worship (with extended hands); intensively, to bemoan (by wringing the hands) — cast (out), (make) confess(-ion), praise, shoot, (give) thank(-ful, -s, -sgiving).

A thorough P&W definition is “to use, hold out the hand, to throw (a stone or arrow) at or away, to revere or worship (with extended hands, praise thankful, thanksgiving)” and a concise definition is “to worship with extended hands.”

The primary root is “to cast with the hand”. That can be applied to shooting arrows (Jeremiah 50:14), throwing a rock (Lamentations 3:53), or expelling someone (Zechariah 1:21). However, the overwhelming majority of uses of this word have nothing to do with literally throwing anything. Instead, we find this word translated as “confess”, or “give thanks”, or “praise”. The connection seems to be in acknowledging one’s guilt by raising hands in identification or surrender (Leviticus 5:5, Numbers 5:7), in expressing thankfulness by pointing toward or marking its object (II Samuel 22:50, Psalm 92:1), or in raised hands to God in giving Him honor (Genesis 29:35, Psalm 33:2).

The issue we have in interpreting the correct meaning of the yadah is determining if the “casting with the hand” root is applied literally/physically, figuratively, or if it is even relevant at all. A similar case I came across a while back is qavah (Strong’s H6960), which implies twisting or binding (as in the strands of a rope), yet is generally translated as “waiting” in Isaiah 40:31. Many Hebrew words have “actions” in them that may be illustrative of the word’s meaning but not always applied in its definition. Sometimes there just isn’t a logical connection to be made.

Another question with yadah is whether the emphasis is on the hand or what the hand casts. Perhaps the emphasis is not on the raised hand in praising God but on the praises that are cast out to Him. An illustration of this is Psalm 33:2, where we find praising (yadah) God with an instrument. Is there literal hand-raising to God, a literal hand extended to the harp, or are the praises being figuratively thrown out towards God? I think this could also make sense in regards to confessing sins in that you are casting your guilt out before others.

I did find reference to Psalm 134:2 in regards to this word (“Lift up your hands in the sanctuary”), but the actual word yadah is not used here. Two other words are: nasa (Strong’s H5375) meaning “to lift” and yad (Strong’s H3027) meaning “hand”. On closer examination, this particular reference in Psalm 134 does not support the ideas of P&W . This is an exhortation to the priests serving at night time in the Temple, not to the congregation of Israel (vs. 1). Any study of nightly activities in the Temple will not show any times of exuberant praise. It must be also noted that in the language of Psalmody that nighttime is a time of darkness and despair, not joy and happiness. The general understanding of the lifting of hands here and in general is that of prayer and not praise (see commentaries here and here).

A deeper look at many of the proof texts of raising hands in joyous worship are actually in context speaking of something quite different (see here for a further discussion of this). We actually see the lifting of hands as a sign of lamentation or desperation in places such as Psalm 28:2, 63:4, 141:2, and Lamentations 2:19, 3:41. A few other references like Genesis 14:22 and Deuteronomy 32:40 have the lifting of hands as part of taking a oath. While these references may not be the focus of our present study, it is important to note they fail to show the lifting of hands in exuberant praise.

For further reference, here is someone that goes a bit deeper in the Hebrew.

Tehillah

- Hebrew: תְּהִלָּה

- Noun

- Strong’s: H8416 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 57x total, 30x in Psalms

- KJV translations: praise (57x).

- Strong’s definition: From halal; laudation; specifically (concretely) a hymn — praise.

One P&W definition is “to sing hallal, a new song, a hymn of spontaneous praise glorifying God in song”. Another (also seen here) includes: “Singing scripture to instruct and encourage”.

Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words (p. 185) highlights four applications of the word. First, it may denote praiseworthiness (Deuteronomy 10:21, Isaiah 62:7). Second, the words or song used to express praise (Psalm 22:22,25). Third, a term for a song (see heading of Psalm 145). Fourth, deeds that are worthy of praise (Exodus 15:11).

I think this definition is clear if you have the definition settled for halal, which we covered before. This is basically the noun form of that verb. It is almost disingenuous to make it a separate word.

What is interesting to me are the two very different additions to the core definition of a song of praise we see in the P&W definitions. One says it is a “spontaneous” song and the other a “scripture” song. Honestly, I think the definition is broad enough to include both cases. I would take exception to the “spontaneous” song if I knew for sure it was used as an expression of prophetic worship (and I assume it is), but that is a whole other subject for another time.

An important appearance of this word is in one of earliest and most frequently used verses as a foundation for P&W theology: Psalm 22:3. I hope to deal with that verse more fully in the future, but I can say that if you see that verse applied to Christian worship I can practically guarantee you are dealing with some Charismatic theology or influence.

Zamar

- Hebrew: זמר

- Verb

- Strong’s: H2167 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 45x total, 41x in Psalms

- KJV translations: praise (26x), sing (16x), sing psalms (2x), sing forth (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root (perhaps ident. With zamar through the idea of striking with the fingers); properly, to touch the strings or parts of a musical instrument, i.e. Play upon it; to make music, accompanied by the voice; hence to celebrate in song and music — give praise, sing forth praises, psalms.

P&W definition #1: “Make music by striking the fingers on strings or parts of a musical instrument. When we play instrumentally to facilitate a holy atmosphere, it’s not just church cocktail music, it’s zamar.”

P&W definition #2: “‘Zamar’ means to pluck the strings of an instrument…. Zamar speaks of rejoicing. It is involved with the joyful expression of music. Zamar means to sing praises or to touch the strings. It speaks of involving every available instrument to make music and harmony before the Lord. It is God’s will that we be joyful. Use Zamar when you are rejoicing after God has done something great for you.”

By itself, zamar means to play a musical instrument (Psalm 33:2, 144:9), but it appears to be a more inclusive word including instrumental and vocal music, probably together. It is interesting to note that zamar occurs in the same (and sometimes adjacent) verses with other praise or musical terms in 39 of its 45 appearances:

- 12x in the same verse with sir (Strong’s H7891, “to sing”) – Judges 5:3, I Chronicles 16:9, Psalm 21:13, 27:6, 57:7, 68:4, 68:32, 101:1, 104:33, 105:2, 108:1, 144:9

- 11x in the same verse with yadah (Strong’s H3034, “to praise”) – II Samuel 22:50, Psalm 7:17, 18:49, 30:4, 30:12. 33:2, 57:9, 71:22, 92:1, 108:3, 138:1

- 1x in close proximity to yadah – Psalm 9:2 (see vs. 1)

- 4x in the same verse with halal (Strong’s H1984, “to praise”) – Psalm 135:3, 146:2, 147:1, 149:3

- 2x in the same verse with nagad (Strong’s H5046, “to declare”) – Psalm 9:11, 75:9

- 2x in the same verse with ranan (Strong’s H7442, “to rejoice”) – Psalm 9:11, 75:9

- 2x in close proximity to ranan – Psalm 59:17 (see vs. 16), Isaiah 12:5 (see vs. 6)

- 2x in the same verse with shachah (Strong’s H7812, “to worship”) – Psalm 66:4 (2x)

- 1x in the same verse with anah (Strong’s H6030, “to answer”) – Psalm 147:7

- 2x in close proximity to rua (Strong’s H7321, “to noise”) – Psalm 66:2 (see vs. 1)

This leaves only the 5x it appears in Psalm 47:6-7 and 1x in Psalm 61:8.

Since the preponderance of uses seem to combine instrumental and vocal terms, I think it is safest to assume it will generally mean a combination of the two. I think the fact that so many other terms appear around it means it is a very generic word.

Examining the P&W definitions, once again the core is close: we are certainly talking about instrumental and vocal music. This is certainly not creating an “atmosphere”: the worshippers here are active and not passive. It is also by no means glorifying “every available instrument”: only specific ones that were acceptable to the Jews are mentioned. I realize this again touches on larger topics that are outside the scope of this study. But that is part of why I am doing this study, because these P&W studies are putting ideas and thoughts into the text (eisegesis) that are simply not there.

Oh, and seriously… “cocktail” music”??? That reference is so absurd. I did need that laugh though.

See also this post.

Taqa

- Hebrew: תָּקַע

- Verb

- Strong’s: 8628 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 69x total, 2x in Psalms

- KJV translations: blow (46x), fasten (5x), strike (4x), pitch (3x), thrust (2x), clap (2x), sounded (2x), cast (1x), miscellaneous (4x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to clatter, i.e. Slap (the hands together), clang (an instrument); by analogy, to drive (a nail or tent-pin, a dart, etc.); by implication, to become bondsman by handclasping) — blow ((a trumpet)), cast, clap, fasten, pitch (tent), smite, sound, strike, X suretiship, thrust.

This one is not found on many of the P&W lists I referenced, but the definition here is “Clap, applaud. Expresses joy and victory.”

Of course the reason why it is not on many lists is because it barely even occurs in context with worship. It is used to “blow a trumpet” 50x, but this is not musical. These trumpet blasts were signals and calls and far more primitive than more modern bugle calls used in the military. There is nothing about making music in these references.

Basically, this verb means to “hit or strike”. Look at its objects when it is used: nails, daggers, tents, darts. When using blowing a trumpet they are just sounding it, or “hitting a note” if I could be pardoned to apply that stretch here.

We have only one true reference to clapping (“striking hands together”) in Psalm 47:1. In Nahum 3:19 someone claps their hand over their mouth but that is quite a different thing. There are two additional references to clapping that use different words: II Kings 11:12, Isaiah 55:12 (see macha). We can see in those that there is a connection between clapping hands and joyous celebration.

Karar

- Hebrew: כָּרַר

- Verb

- Strong’s: 3769 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 2x total, 0x in Psalms

- KJV translations: dance (2x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to dance (i.e. Whirl) — dance(-ing).

Defined simply here for P&W as “Dance. ‘David danced before the Lord with all his might.’ Expresses joy and celebration.“

This word only appears in the account of David celebrating the return of the Ark of the Covenant in II Samuel 6. This is a singular act by a singular person at a singular time. To extrapolate this into a command to dance in worship is unsound at best. There are other words used for dance that we will get to, but since I find this word on a few lists I feel the need to cover it although it is essentially worthless in arguing for charismatic worship.

(I would recommend you reference Scott Aniol’s Changed from Glory into Glory: The Liturgical Story of the Christian Faith, p. 43-45, for better analysis of this. It’s too long for me to post here.)

Tephillah

- Hebrew: תְּפִלָּה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 8605 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 77x total, 32x in Psalms

- KJV translations: prayer (77x).

- Strong’s definition: From palal; intercession, supplication; by implication, a hymn — prayer.

A very straightforward definition found here: “Prayer, often sung as intercession and petition.”

Okay, this the first word that we have looked at that I really don’t have any problem with. It means prayer, spoken (I Kings 8:28) or sung (Psalm 17 heading). Perhaps some P&W teachings go beyond this simple definition but the places I am referencing seem to have this one right if they mention it at all.

Todah

- Hebrew: תּוֹדָה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 8426 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 32x total, 12x in Psalms

- KJV translations: thanksgiving (18x), praise (6x), thanks (3x), thank offerings (3x), confession (2x).

- Strong’s definition: From yadah; properly, an extension of the hand, i.e. (by implication) avowal, or (usually) adoration; specifically, a choir of worshippers — confession, (sacrifice of) praise, thanks(-giving, offering).

A P&W definition found here: “an extension of the hand, avowal, adoration, a choir of worshipers, confession, sacrifice of praise, thanksgiving”

Basically we have here the noun form of yadah. I will refer you to the previous examination of that word.

(Honestly, you can tell some of the foundation for these lists of “Hebrew words for worship” just got the words from a Strong’s concordance without really digging into them at all. Otherwise, words like todah and yadah would be classified together. See this article which couples todah, not with yadah as would be logically and grammatically correct, but with shabach.)

See also this post.

Shachah

- Hebrew: שָׁחָה

- Verb

- Strong’s: 7812 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 172x total, 17x in Psalms

- KJV translations: worship (99x), bow (31x), bow down (18x), obeisance (9x), reverence (5x), fall down (3x), themselves (2x), stoop (1x), crouch (1x), miscellaneous (3x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to depress, i.e. Prostrate (especially reflexive, in homage to royalty or God) — bow (self) down, crouch, fall down (flat), humbly beseech, do (make) obeisance, do reverence, make to stoop, worship.

Your P&W definition, found here and here: “to depress or prostrate in homage or loyalty to God, bow down, fall down flat”

When we discuss worship I believe this is the key word. In a secular sense (which is about half of its uses), it means to “bow down”, as one would do in reverence to a ruler (Genesis 42:6, Esther 3:2). It is is sign of humility on the one bowing down and a sign of honor to the one bowed down to. It also implies service to something (Exodus 20:5).

This is not loud or ecstatic. It is quiet. It is not celebratory. It is reverential. It is not proud. It is humble. It is not accidental. It is intentional.

I like the image of bowing down. It puts all the glory and honor on the one being worshipped and not on the worshipper. We bow ourselves out of the picture and let all the attention and glory go to God. We worship according to His commands and expectations, not our own. That is true worship.

It does not require a band. It does not require being worked up into frenzy. It does not require a precursory time of praise. It does not require being at a church or even gathered with other believers. We simply acknowledge our ever-present God and His ceaseless majesty.

(Can you tell I preached a sermon on this not too long ago?)

Shir

- Hebrew: שִׁיר

- Verb

- Strong’s: 7891 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 87x total, 27x in Psalms

- KJV translations: sing (41x), singer (37x), singing men (4x), singing women (4x), behold (1x).

- Strong’s definition: Or (the original form) shuwr (1 Sam. 18:6) {shoor}; a primitive root (identical with shuwr through the idea of strolling minstrelsy); to sing — behold (by mistake for shuwr), sing(-er, -ing man, – ing woman).

A rather simple P&W definition found here: “strolling minstrelsy, to sing, singer (man or woman)”

This one is another very direct and basic word that essentially means “to sing”. The only real headscratcher to me is Strong’s addition of “strolling minstrelsy”, which appears to come from a similar root shur (Strong’s H7788) which means to journey or travel. I am not so certain this word means anything about being minstrel but may rather be a description of singing (changing tones and moving rhythms), perhaps related to the term shiggaion (Strong’s 7692). Again, I am no expert here, but I am not seeing anything similar to “strolling minstrelsy” in other reference works.

Alats

- Hebrew: עָלַץ

- Verb

- Strong’s: 5970 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 8x total, 4x in Psalms

- KJV translations: rejoice (6x), joyful (1x), triumph (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to jump for joy, i.e. Exult — be joyful, rejoice, triumph.

This is another case where the action part of the word may be more figurative than literal. For instance, Hannah said: “My heart rejoiceth [alats] in the LORD” (I Samuel 2:1) We have a similar expression today in saying “our hearts leap for joy” which is figurative.

Alaz

- Hebrew: עָלַז

- Verb

- Strong’s: 5937 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 16x total, 7x in Psalms

- KJV translations: rejoice (12x), triumph (2x), joyful (2x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to jump for joy, i.e. Exult — be joyful, rejoice, triumph.

A similar word and case to alats.

Anah

- Hebrew: עָנָה

- Verb

- Strong’s: 6030 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 329x total, 39x in Psalms

- KJV translations: answer (242x), hear (42x), testify (12x), speak (8x), sing (4x), bear (3x), cry (2x), witness (2x), give (1x), miscellaneous (13x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; properly, to eye or (generally) to heed, i.e. Pay attention; by implication, to respond; by extens. To begin to speak; specifically to sing, shout, testify, announce — give account, afflict (by mistake for anah), (cause to, give) answer, bring low (by mistake for anah), cry, hear, Leannoth, lift up, say, X scholar, (give a) shout, sing (together by course), speak, testify, utter, (bear) witness. See also Beyth ‘Anowth, Beyth ‘Anath.

Nothing crazy here. Basically means “to give attention to or answer”.

Chagag

- Hebrew: חָגַג

- Verb

- Strong’s: 2287 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 16x total, 2x in Psalms

- KJV translations: keep (8x), …feast (3x), celebrate (1x), keep a solemn feast (1x), dancing (1x), holyday (1x), reel to and fro (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root (compare chagra’, chuwg); properly, to move in a circle, i.e. (specifically) to march in a sacred procession, to observe a festival; by implication, to be giddy — celebrate, dance, (keep, hold) a (solemn) feast (holiday), reel to and fro.

This means “to keep a religious festival or ritual”. The first reference in Psalms means to participate in or observe a Jewish festival (Psalm 42:4). The second means to dance or move as a drunk person (Psalm 107:27). Wide variety in those two.

Chuwl

- Hebrew: חוּל

- Verb

- Strong’s: 2342 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 62x total, 12x in Psalms

- KJV translations: pain (6x), formed (5x), bring forth (4x), pained (4x), tremble (4x), travail (4x), dance (2x), calve (2x), grieved (2x), grievous (2x), wounded (2x), shake (2x), miscellaneous (23x).

- Strong’s definition: Or chiyl {kheel}; a primitive root; properly, to twist or whirl (in a circular or spiral manner), i.e. (specifically) to dance, to writhe in pain (especially of parturition) or fear; figuratively, to wait, to pervert — bear, (make to) bring forth, (make to) calve, dance, drive away, fall grievously (with pain), fear, form, great, grieve, (be) grievous, hope, look, make, be in pain, be much (sore) pained, rest, shake, shapen, (be) sorrow(-ful), stay, tarry, travail (with pain), tremble, trust, wait carefully (patiently), be wounded.

Used for “dance” in Judges 21 and nowhere else. Has the idea of “writhing” or “shaking”. The uses in Psalms are not noteworthy in our present study as they do not refer to worship.

Qol

- Hebrew: קֹל

- Noun

- Strong’s: 6963 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 506x total, 57x in Psalms

- KJV translations: voice (383x), noise (49x), sound (39x), thunder (10x), proclamation (with H5674) (4x), send out (with H5414) (2x), thunderings (2x), fame (1x), miscellaneous (16x).

- Strong’s definition: Or qol {kole}; from an unused root meaning to call aloud; a voice or sound — + aloud, bleating, crackling, cry (+ out), fame, lightness, lowing, noise, + hold peace, (pro-)claim, proclamation, + sing, sound, + spark, thunder(-ing), voice, + yell.

Basically means the sound something makes. Could be an animal (I Samuel 15:14), thunder (I Samuel 12:18), or water (Psalm 42:7). It does not necessarily mean something is loud, but doesn’t rule it out either. In many uses it means the human voice (Genesis 3:7, Psalm 3:4) or even God’s voice (Genesis 3:8, Psalm 103:20).

Kabad

- Hebrew: כָּבַד

- Verb

- Strong’s: 3513 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 116x total, 11x in Psalms

- KJV translations: clap (3x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to rub or strike the hands together (in exultation) — clap.

“To be heavy”. Can be in the sense of honor (Exodus 20:12, Daniel 11:38) or glory (Leviticus 10:3, Psalm 22:23). Can be negative in these sense of hardening a heart (Exodus 8:15, I Samuel 6:6) or something extreme (Genesis 18:20, Isaiah 9:1). The most common use in Psalms is to denote glory (Psalm 86:9,12).

Macha

- Hebrew: מָחָא

- Verb

- Strong’s: 4222 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 3x total, 1x in Psalms

- KJV translations: honour (34x), glorify (14x), honourable (14x), heavy (13x), harden (7x), glorious (5x), sore (3x), made heavy (3x), chargeable (2x), great (2x), many (2x), heavier (2x), promote (2x), miscellaneous (10x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to rub or strike the hands together (in exultation) — clap.

Used twice for anthropomorphic clapping (Psalm 98:8, Isaiah 55:12). I suppose someone may say those set some sort of precedent for clapping in worship since the rivers and trees are seen doing it, but there are better verses to build that case with. I would like to point out that both also appear to picture the earth celebrating the arrival of the Millennial Kingdom.

Used once for Ammon celebrating the Jew’s despair (Ezekiel 24:6).

Machowl

- Hebrew: מָחוֹל

- Noun

- Strong’s: 4234 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 6x total, 3x in Psalms

- KJV translations: dance (5x), dancing (1x).

- Strong’s definition: From chuwl; a (round) dance — dance(-cing).

The noun form of chuwl. Scott Aniol in Changed from Glory into Glory (p. 43-44) states that is is the only Old Testament term that corresponds to what we call dancing today. He describes it as a joyful folk dance of celebration. It is used to convey the idea of utter joy (Psalm 30:11, Jeremiah 31:13, Lamentations 5:15)

I also want to go ahead and note that the plural form of the word, mechowlah (Strong’s H4246) is used to describe the celebratory dancing after crossing the Red Sea (Exodus 15:20), Japhthah’s victory over Ammon (Judges 11:34), David’s victory over Goliath, (I Samuel 18:6, 21:11, 29:5) and in a more negative context in the worship of the golden calf (Exodus 32:19). Scott Aniol does not differentiate between the singular and plural forms in his discussion. That isn’t a problem at all, but someone not paying attention and cross-referencing with a concordance may be confused since there will be multiple Strong’s numbers in play.

In discussing the uses of machowl and mecholah in Psalm 149:3 and 150:4, Aniol points out that the emphasis is not necessarily on corporate worship but rather on praising God at all time. In Psalm 149 for example, we see the times of praise including while the congregation is assembled (vs. 1), while the saints are resting in their beds (vs. 5), and while the nation is at war (vs. 6-9). In Psalm 150 we see praising God in His sanctuary (vs. 1) but also a command that every living thing should praise the Lord (vs. 6) which is a much broader application.

Mechowlah

- Hebrew: מְחֹלָה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 4246 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 8x total, 0x in Psalms

- KJV translations: dance (5x), dancing (2x), company (1x).

- Strong’s definition: Feminine of machashabah; a dance — company, dances(-cing).

See previous notes on machowl. This is the the plural form of that word and is referenced in that discussion.

Nasa

- Hebrew: נָסָה

- Verb

- Strong’s: 5375 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 654x total, 48x in Psalms

- KJV translations: (bare, lift, etc…) up (219x), bear (115x), take (58x), bare (34x), carry (30x), (take, carry)..away (22x), borne (22x), armourbearer (18x), forgive (16x), accept (12x), exalt (8x), regard (5x), obtained (4x), respect (3x), miscellaneous (74x).

- Strong’s definition: Or nacah (Psalm ‘eb: ‘abad (‘abad)) {naw-saw’}; a primitive root; to lift, in a great variety of applications, literal and figurative, absol. And rel. (as follows) — accept, advance, arise, (able to, (armor), suffer to) bear(-er, up), bring (forth), burn, carry (away), cast, contain, desire, ease, exact, exalt (self), extol, fetch, forgive, furnish, further, give, go on, help, high, hold up, honorable (+ man), lade, lay, lift (self) up, lofty, marry, magnify, X needs, obtain, pardon, raise (up), receive, regard, respect, set (up), spare, stir up, + swear, take (away, up), X utterly, wear, yield.

A general verb meaning “to bear or carry”. In Psalms it used in many ways, including to lift up heads (Psalm 24:7), lift up hands (Psalm 28:2), bearing reproach (Psalm 69:7) taking or bringing (Psalm 72:3, 81:2), lifting up soul (Psalm 86:4), forgiving (Psalm 99:8), and lifting up eyes (Psalm 121:1). I think there usage is too varied to draw any concrete conclusions about worship solely from this word.

Nagan

- Hebrew: נָגַן

- Verb

- Strong’s: 5059 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 15x total, 2x in Psalms

- KJV translations: play (8x), instrument (3x), minstrel (2x), melody (1x), player (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; properly, to thrum, i.e. Beat a tune with the fingers; expec. To play on a stringed instrument; hence (generally), to make music — player on instruments, sing to the stringed instruments, melody, ministrel, play(-er, -ing).

Means “to play an instrument” and by extension “those that play instruments.” Nothing earthshattering here.

Neginah

- Hebrew: נְגִינָה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 5058 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 14x total, 9x in Psalms

- KJV translations: Neginoth (6x), song (5x), stringed instruments (1x), musick (1x), Neginah (1x).

- Strong’s definition: Or ngiynath (Psa. ‘abal:title) {neg-ee-nath’}; from nagan; properly, instrumental music; by implication, a stringed instrument; by extension, a poem set to music; specifically, an epigram — stringed instrument, musick, Neginoth (plural), song.

Means “music of stringed instruments.” Found in the headings of multiple Psalms (4, 6, 54, 55, 61, 67, 76) to note that those songs had musical accompaniment. The idea of musical accompaniment is also seen in Isaiah 38:20. There are a few cases that in their context show their music to be satirical or mocking in nature (Job 30:9, Psalm 69:12, Lamentations 3:14), but these applications shouldn’t define the other uses.

Patsach

- Hebrew: פָּצַח

- Verb

- Strong’s: 6476 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 8x total, 1x in Psalms

- KJV translations: break forth (6x), break (1x), make a loud noise (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to break out (in joyful sound) — break (forth, forth into joy), make a loud noise.

This is a case where the Strong’s definition is taking into account the object or effects of the verb and ignoring the words actual meaning. Patsach means “to break or to burst”, as in the breaking of bones in Micah 3:3. It can then have an object that says what is breaking out. Five of the uses involve the anthropomorphic descriptions of the earth or nature “breaking out” and singing coming forth (Psalm 98:4, Isaiah 14:7, 44:23, 49:13, 52:9, 55:12). The lone use where it is people breaking out in song is Israel in Isaiah 54:1. It would be hard to apply this to our worship.

Pazaz

- Hebrew: פָּזַז

- Verb

- Strong’s: 6339 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 2x total, 0x in Psalms

- KJV translations: made strong (1x), leaping (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root (identical with pazaz); to solidify (as if by refining); also to spring (as if separating the limbs) — leap, be made strong.

Strong’s definition is almost longer than the verses this word appears in. The NAS Exhaustive Concordance make it far more concise: “to be supple or agile”.

There are only two uses of this word in Hebrew Scripture. The first is in Genesis 49:24 in Jacob’s blessing of Joseph speaking figuratively about Joseph’s strength as being enhanced by God using the imagery of pulling back a bow string.

The second is when David was “leaping” as he danced before the arriving Ark of the Covenant in II Samuel 6:16. That lone appearance is why this word may appear on some of the more exhaustive P&W lists. For a deeper look at David’s dancing, see notes on karar.

Raqad

- Hebrew: רָקַד

- Verb

- Strong’s: 7540 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 9x total, 3x in Psalms

- KJV translations: dance (4x), skip (3x), leap (1x), jump (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; properly, to stamp, i.e. To spring about (wildly or for joy) — dance, jump, leap, skip.

The best idea of this word is “skipping, jumping, or leaping”. We see chariots bouncing at high speed (Nahum 3:2, Joel 2:5), the children of the wicked dancing or jumping around (Job 21:11), animals leaping about (Isaiah 13:21), and anthropomorphized mountains and trees skipping like animals (Psalm 114:4, 114:6, Psalm 29:6).

I want to examine the two remaining cases where it means “dancing”. The first I want to note is in Ecclesiastes 3:4 where joyful dancing is the opposite of mourning. This is not prescriptive but descriptive.

The second case is, of course, David dancing before the Ark in I Chronicles 15:29. For a deeper look at David’s dancing, see notes on karar. (Spoiler: its not a command or example we are called to follow.)

Renanah

- Hebrew: רְנָנָה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 7445 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 4x total, 2x in Psalms

- KJV translations: joyful voice (1x), joyful (1x), triumphing (1x), singing (1x).

- Strong’s definition: From ranan; a shout (for joy) — joyful (voice), singing, triumphing.

The connotation of this word adds the idea of “rejoicing or joyfulness”. The two occurrences in Job 3:7 and 20:5 are not instructive in a study on worship. The two references in Psalm 63:5 and 100:2 are instructive that we should joyfully praise or God.

Rinnah

- Hebrew: רִנָּה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 7440 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 33x total, 15x in Psalms

- KJV translations: cry (12x), singing (9x), rejoicing (3x), joy (3x), gladness (1x), proclamation (1x), shouting (1x), sing (1x), songs (1x), triumph (1x).

- Strong’s definition: From ranan; properly, a creaking (or shrill sound), i.e. Shout (of joy or grief) — cry, gladness, joy, proclamation, rejoicing, shouting, sing(-ing), triumph.

This word can be an expression of grief (Psalm 106:44, 142:6) or joy (Psalm 30:5, 126:5). Roughly 1/3 of the uses are expressing grief or desperation.

Rua

- Hebrew: רוּעַ

- Noun

- Strong’s: 7321 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 46x total, 12x in Psalms

- KJV translations: shout (23x), noise (7x), ..alarm (4x), cry (4x), triumph (3x), smart (1x), miscellaneous (4x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to mar (especially by breaking); figuratively, to split the ears (with sound), i.e. Shout (for alarm or joy) — blow an alarm, cry (alarm, aloud, out), destroy, make a joyful noise, smart, shout (for joy), sound an alarm, triumph.

Rua essentially means “to shout” but is applied in varied ways. It is the shout of Israel when the circled Jericho in Joshua 6. It can be a cry of alarm (Numbers 10:7, Joel 2:1). It can mean shouting in triumph (Psalm 41:11, 108:9), which can also mean defeat (Proverbs 13:20).

As far as the uses in Psalms, we see shouting for victory and joy (Psalm 47:1, 65:13), the aforementioned triumphs (Psalm 41:11, 108:9), or the “joyful noise” (Psalm 66:1, 81:1, 95:1, 95:2, 98:4, 98:6, 100:1). To read more about the “joyful noise”, here is an GotQuestions.org article. I may need to revisit that in a future study.

Samach

- Hebrew: שָׂמַח

- Verb

- Strong’s: 8055 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 152x total, 52x in Psalms

- KJV translations: shout (23x), noise (7x), ..alarm (4x), cry (4x), triumph (3x), smart (1x), miscellaneous (4x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; probably to brighten up, i.e. (figuratively) be (causatively, make) blithe or gleesome — cheer up, be (make) glad, (have, make) joy(-ful), be (make) merry, (cause to, make to) rejoice, X very.

This word means to “to rejoice” or “be glad or happy”. Not any controversy here that I see.

Sason

- Hebrew: שָׂשׂן

- Noun

- Strong’s: 8342 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 22x total, 5x in Psalms

- KJV translations: joy (15x), gladness (3x), mirth (3x), rejoicing (1x).

- Strong’s definition: Or sason {saw-sone’}; from suws; cheerfulness; specifically, welcome — gladness, joy, mirth, rejoicing.

Pretty clear. No comments needed.

Raam

- Hebrew: רָעַם

- Verb

- Strong’s: 7481 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 13x total, 4x in Psalms

- KJV translations: thunder (8x), roar (3x), trouble (1x), fret (1x).

- Strong’s definition: A primitive root; to tumble, i.e. Be violently agitated; specifically, to crash (of thunder); figuratively, to irritate (with anger) — make to fret, roar, thunder, trouble.

I’ll be honest and I say that I don’t recall which list I saw this word on. I thought it was maybe here but its not. It must have ended on my list for a reason so I will go ahead and look at it.

This word means “to roar or thunder” or by extension “to tremble”. We see the roar of the sea (I Chronicles 16:32, Psalm 96:11, 98:7), literal thunder from the sky (I Samuel 2:10, 7:10), and God’s voice associated with thunder (Job 37:4-5, 40:9, II Samuel 22:14, Psalm 18:13, 29:3). The two references to being troubled or trembling are in I Samuel 1:6 and Ezekiel 27:35.

That’s all. Not sure why this would appear in a P&W Hebrew word list but I guess it did somewhere to make it on my list.

Shaon

- Hebrew: שָאוֹן

- Noun

- Strong’s: 7588 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 17x total, 4x in Psalms

- KJV translations: noise (8x), tumult (3x), tumultuous (2x), rushing (2x), horrible (1x), pomp (1x).

- Strong’s definition: From sha’ah; uproar (as of rushing); by implication, destruction — X horrible, noise, pomp, rushing, tumult (X -uous).

Picture a “tumultuous uproar” and that fits practically every appearance. This is never applied to praise to God and never used in a positive sense.

Though it appears on a list here, the listed references do not even contain the word (they appear to be for rua). Not sure why it would be listed unless they are pushing an idea of tumultuous or uproarious worship but the word is never used in a way to support that idea.

Shiyr

- Hebrew: שִׁירָה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 7892 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 89x total, 43x in Psalms

- KJV translations: song (74x), musick (7x), singing (4x), musical (2x), sing (1x), singers (1x), song (with H1697) (1x).

- Strong’s definition: Or feminine shiyrah {shee-raw’}; from shiyr; a song; abstractly, singing — musical(-ick), X sing(-er, -ing), song.

A generic word for “song, singing, or music”. I’ve got nothing to add. Moving on…

Sus

- Hebrew: שׂוּשׂ

- Verb

- Strong’s: 7797 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 27x total, 9x in Psalms

- KJV translations: rejoice (20x), glad (4x), greatly (1x), joy (1x), mirth (1x).

- Strong’s definition: Or siys {sece}; a primitive root; to be bright, i.e. Cheerful — be glad, X greatly, joy, make mirth, rejoice.

Another straightforward definition. I’ve got nothing to add.

Teruah

- Hebrew: תְּרוּעָה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 8643 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 36x total, 5x in Psalms

- KJV translations: shout (11x), shouting (8x), alarm (6x), sound (3x), blowing (2x), joy (2x), miscellaneous (4x).

- Strong’s definition: From ruwa’; clamor, i.e. Acclamation of joy or a battle-cry; especially clangor of trumpets, as an alarum — alarm, blow(- ing) (of, the) (trumpets), joy, jubile, loud noise, rejoicing, shout(-ing), (high, joyful) sound(-ing).

Noun form of rua. I will refer you to that previous study for the meaning here.

Zimrah

- Hebrew: תְּרוּעָה

- Noun

- Strong’s: 2172 – BibleHub – SudyLight – BlueLetterBible

- Uses: 4x total, 2x in Psalms

- KJV translations: melody (2x), psalm (2x).

- Strong’s definition: From zamar; a musical piece or song to be accompanied by an instrument — melody, psalm.

Noun form of zamar. I will refer you to that previous study for the meaning here.